By: Travis Allen

Travis is away this week, so we’re re-running the second part of his two-part series about MTGO. He will return next week on the 21st.

This week is part two of a two-part series on the failure of the MTGO marketplace. You can find part one here. The tl;dr from last week is that Magic cards behave like commodities, and thus are eligible for a unique type of online market.

Upon entering a convention hall hosting a Grand Prix you’ll notice vendors ringing the space. The vendors, of whom there are usually between five and eight, each have different numbers for their buy and sell prices. If our intrepid player – let’s say you – decides he wants to buy the cheapest Glittering Wish in the room he’s going to have to do some legwork. Finding the least expensive copy is going to require visiting every single booth, muscling through the mob, locating the card in the case, and checking the price tag. Then you’ll need to repeat that entire sequence about seven more times. Once you’ve checked all eight vendors and have identified the cheapest copy, it’s finally time to go make a purchase. Let’s hope that they haven’t sold out while you were checking each other price in the room!

Imagine instead that there are not eight vendors in the room, but 50,000. Welcome to the Magic Online classifieds.

The unwieldy system for buying and selling cards at a GP is as it is because there is no centralized method for buying and selling paper cards in a meatspace. There is no single booth in the room that you can walk up to that sells cards on behalf of every vendor present. You’re forced to manually check with each one. This problem only becomes wildly more intense when add in the fact that not only can you buy the card from a vendor, but there are a few thousand binders in the room that are more than willing to trade. Somewhere amongst those eight vendors and 2,000 players is the theoretical cheapest copy of Glittering Wish, but there is basically no chance you’re actually going to find it. At the same time, someone in that room will give you fifteen dollars cash for your Courser of Kruphix (market value $15.76), but good luck finding the guy. It’s far more likely that you’ll take the seven to ten bucks one of the vendors is offering.

Such a system is brutally inefficient. There is no convenient method for buyers and sellers to see all the options available to them. There is no central structure in place through which all information is available to all parties at once. This is one of the myriad of reasons that real life sucks.

The solution to such a burdensome and inefficient system is to create some sort of hub of activity through which all transactions flow. A system that is capable of gathering all of the values of every unique card, for both sale and purchase, that is also fully queryable would do dramatic things to the market. By necessity such a system would immediately wipe out all transactions in which one party was getting more than their fair share. Third party vendors would disappear, and cards would flow freely among the vast majority of agents in the room: the players.

Magic Online is capable of this. There is only one MTGO server every single person in the world logs into. Whether you’re a bored housewife in Spain, an unemployed roustabout in Ukraine, or a pissy adolescent in the Nebraska plains, if you want to play MTGO you’re all going to the same place. This affords a fantastic opportunity that is not available to paper players: a true commodity marketplace.

MTGO puts every single player in the same system. You all have access to the same tournaments and classifieds. The foundation is in place to provide an efficient, fast, and fair marketplace for the commodity market that is Magic cards. Instead, you’re forced to bumble around blindly in a room of tens of thousands of vendors because….well, I have no idea why.

Because MTGO has failed to provide an adequate market for their playerbase, it has resulted in less-than-ideal conditions. If you’re a player on MTGO and you want to buy a Courser, you hit the classifieds and search for Courser of Kruphix. A list appears of everyone who has the phrase “Courser of Kruphix” in their title. (Remember too that “Courser of Kruphix” is different than “Courser,” so you’d better hope you’re using the same terminology as everyone else in the room.) If you’re lucky they put their sale price for Courser in the title of the classified as well, but not all will. Any that don’t have the sale price in the title will require opening a trade. This will have to happen several times before you can begin to get a feel for what the ‘average’ price of a Courser is so that when you actually find a good price you’ll know it.

There are a variety of pitfalls in this model. For instance, what happens if someone is selling their Courser for 20% less than everyone else, but accidentally spelled it “Cuorser?” How about the individual selling more than three different uniquely named cards? How is he supposed to advertise all of those as being for sale? The classified title has a character limit of course, so you can really only advertise your hottest items. This means it’s tough for someone to expose good prices on more off-beat cards, and it’s tough for buyers because they’re forced to just start wading through random trade binders to find a good price for a card. Sellers can’t adequately advertise their stock or even let people know what they’re selling, and buyers have trouble finding people who are selling what they want. Imagine going to a mall but instead of each store having large glass windows displaying their product they were all painted black.

What MTGO has done is effectively turn every player into a vendor in the same room. It’s hard to imagine a worse way to go about things. This frustratingly cumbersome system results in the creation of an automated process; the bot network. Anyone that plays with any regularity on MTGO is very familiar with bots. They’re awake twenty-four hours a day, have huge inventories, and are (mostly) easy to deal with. They exists to fill the massive exchange gap that MTGO continues to let exist. Imagine for a moment that MTGO banned bots. If you wanted to sell your Courser for tickets, the only way to do so would be to find another individual online at exactly that time that is willing to pay the price you’re asking. This doesn’t sound too bad for a hot staple like Courser, which will move quickly, but what if you’re trying to sell something like a foil Tangle Wire? What do you think the odds are that both someone selling and someone buying are online at the same time, that the seller is currently advertising that card in the classifieds, and that they can both agree on a price? This is exactly why bots exist.

Bots fill a gap, and whenever a service does so, the guy running the service is making a profit on every exchange. It’s the same way your LGS makes money buying and selling cards. Give players a little bit less for their cards than another average player would, and sell them for slightly more than the average player would. The reason anyone uses the service at all is not because they love getting ripped off, but because they’re paying for the convenience of having another market actor who will engage in 99% of transactions at nearly any time. Connecting buyer to seller is a profitable market to be in.

MTGO isn’t like real life, though. Computers aren’t hampered by the need to sleep or eat or otherwise be away from a market. They also can connect thousands and thousands in one central room with quick, easy transactions in a way that no real life environment could imitate. Why, when the system is already in place to provide the best possible market to the average player, does MTGO not capitalize on it?

The problem is compounded by the fact that tickets can’t be split. I’m sure Wizards has their own arcane reason for this, but the result is disastrous for players. By refusing to allow tickets to be split out to a hundredth of a decimal place, MTGO is essentially saying that no card can theoretically be worth less than one ticket. After all, if one ticket is the bare minimum official currency, how does one buy something that costs less than that?

Most commons, uncommons, and even rares for that matter, are worth less than one ticket on the MTGO market. Good luck trying to trade these easily between players though. Let’s say you want to acquire two copies of Restore Balance but without going through a bot. We have all the issues from before of actually finding someone who has two copies of this, but then how do you trade? You don’t want to pay a full ticket for what is worth maybe half a ticket at absolute best. This means you’ve either got to buy cards you don’t want, or the other agent has to take roughly half a tickets worth of value from you. Meanwhile all of this takes time and effort, and why is the guy with the Restore Balances going through all of this in the first place? It certainly isn’t worth his time for the what, tenth of a ticket worth of value he may get out of the transaction?

Bot networks are further supported by MTGO’s refusal to allow tickets to be split. They provide virtual ticket splitting by offering credit to players. Head over to your nearest preferred bot, trade him your cards, and you get credit out to multiple decimal places that can then be used anywhere on that bot network. This of course incentivizes players to keep returning to the same bot network over and over, lest they end up with ten tickets worth of credit spread out among ten different vendors. It’s the “forty-eight cents left on this gift card” syndrome all over again. The nature of the integer ticket is ultimately great for bots and terrible for the average player.

Let’s review. MTGO has the foundation in place to provide an excellent market experience that would be literally impossible to replicate in the real world. A commodity network on MTGO would overall reduce the prices players pay for their cards, overall increase how much they sell their cards for, and overnight get rid of bot networks. For 99.99% of people in the system it’s a complete upgrade. So what needs to change to get us there, and what does “there” look like?

First of all the ticket system has to be fixed. Without the ability for players to reduce tickets to the second decimal place, essentially setting the minimum price on a card to a single cent, then none of this will work. When a huge chunk of the market is worth less than the smallest division of your currency, all sorts of weird problems will pop up. (Like bot networks offering credit that relies entirely on the buyer placing unfounded trust in an unaccountable stranger.)

The next step is basically to completely get rid of the classifieds as you know them. Gone. They will instead be replaced by a central commodity market that essentially functions as a miniature auction for every single type of good. These types of virtual markets already exist all over the place. We’ll take a look at a pretty big one that’s arguably the most successful: the Steam market.

Welcome to the Steam Community Market. On arrival we see what I currently have for sale, when I listed it, and how much I’m asking for it. Below that are a list of the most popular items today. For right now we want to buy Jarate, an item used by the sniper in Team Fortress 2. For the rest of this demonstration, just imagine replacing the word “Jarate” with “Wrath of God” and the process is exactly how MTGO could work.

I’m going to plug in Jarate in the search field over there on the right, and this is what I see after:

Here’s a list of everything with Jarate in the name. You’ll see there are various types of Jarate – Vintage, Strange, Festive, Collector’s, etc. Imagine these as being “10th Edition, 9th Edition, 7th Edition Foil, FTV:Armageddon, etc.” Let’s take a look at the festive Jarate.

I get to see a big image of what I’m purchasing, along with a description that would probably be oracle text if this was an actual Magic card. Below I have a graph of the history of sales data for this product, with samples across multiple timespans, and below that all the Festive Jarates for sale. Because Festive Jarate is a commodity – every instance of it is basically the exact same as all the others – the listings automatically sort by the only defining characteristic: the price. I see how much it is, who’s selling it, and most importantly, for how much. Let’s buy one.

Clicking “Buy Now” gives me a confirmation box, showing again exactly what I’m getting, how much I’m paying for it, and how my money is being spent. Notice Steam even gets to take a little off the top for providing the transaction. That’s a nice incentive for Wizards that doesn’t exist in the current MTGO classifieds system.

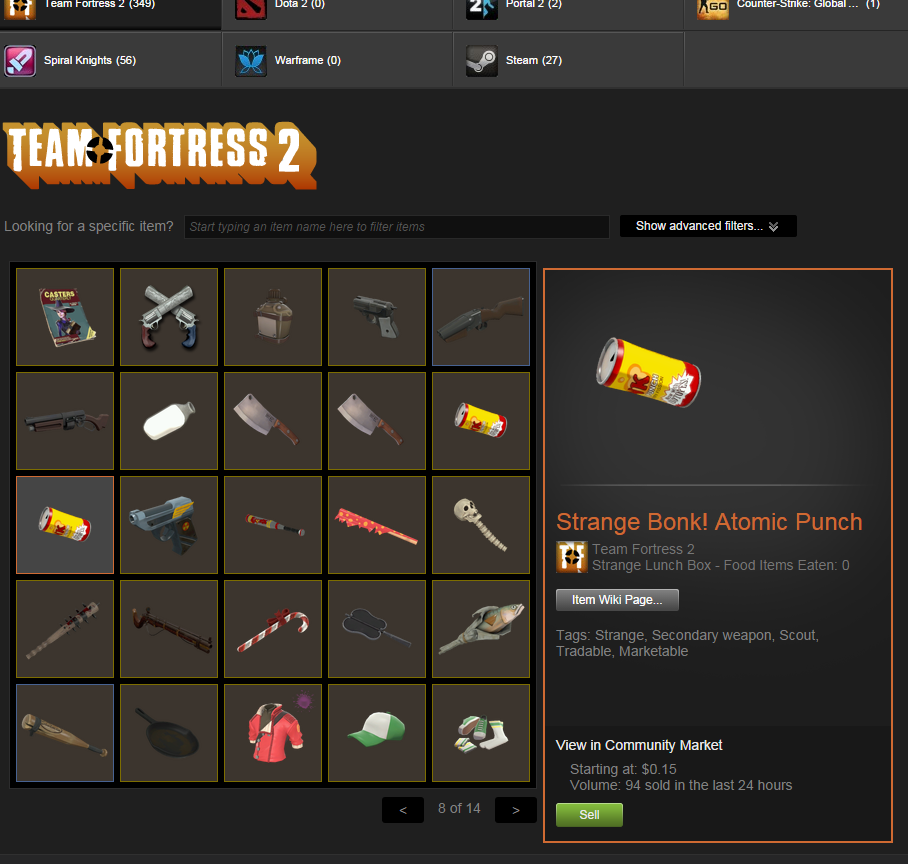

How about if I want to sell something on the market? If I’m browsing my backpack (or MTGO collection) and discover I have something I don’t need, selling it is eazy peazy.

Simply clicking on the item shows me the cheapest price for the product on the market as well as how many copies have sold in the last twenty-four hours.

Clicking the “Sell” button shows another price graph, and allows me to price the product in one of two ways: how much the buyer will pay, or how much I want to actually pocket after its sale.

These two examples show just how easy buying and selling in the MTGO marketplace could be. Need a Rattleclaw Mystic? Hop on the market, search it up, and find the cheapest four copies on MTGO immediately. Browsing through your binder and realize you’ve only got three Polukranos? Click on the existing card in your inventory and buy the card right from your binder. Find an extra copy of Mantis Rider you don’t need as you’re putting together a list? Put it up for sale right from your binder. You don’t even have to leave the page! A simple pop-up window will handle the ease of listing the card.

The ease of buying and selling isn’t the only logistical advantage for the player. A model of this sort would allow the creation of buy and sell orders. Suppose there’s a card you want to spec on – maybe Spellweaver Volute or something wacky. You can create what’s known as a buy order. Tell the system exactly what card you want, how much you want to pay for it, and how many copies you want. Every time a Spellweaver Volute is listed at or below your designated price, your account automatically buys the card until the quota is filled. How amazing would it be to set prices for all these cards you need at low prices and then a week later have them?

If buy orders aren’t cool enough, how about MTGO telling you in real time how much it would cost to buy the cards you don’t currently own from a given decklist? Log into the mothership with your MTGO account info, and the next time Gavin posts a sweet brew there will be a dollar vlaue right there telling you how much it would cost to buy the cards missing from your account. “This is an awesome Junk reanimator list, and it would only be about seventy bucks to finish it. I’m going to go build it.”

A feature-rich commodity market such as what I’ve discussed and shown you here would have some large consequences. Bots would disappear overnight, which would admittedly suck for the guys over at MTGOTraders and such. That’s an acceptable loss if it means better prices for players across the board. Cards would find their equilibriums faster. Spreads would shrink to the smallest they’ve ever been. Gone would be the days of spikes causing cards to be difficult to find for less-than-insane prices. Players would more easily be able to switch between decks, because the cost of selling out of one list and buying into another would be so low. The metagame would become truly fluid, as players could easily and affordably build the best deck for each tournament, not just the best deck in their card pool. It would be a revitalization of the entire MTGO ecosystem.

MTGO has no shortage of problems, as many of my peers have written about. Twitter is fully of daily lamentations from fish and pros alike. Screenshots of ridiculous bugs circulate regularly. At least once a month someone writes an article about some other part of MTGO that is awful, such as the compensation policy or terrible payouts. While all of these are valid and frustrating complaints, few reveal a fundamental flaw in Wizard’s appreciation for their content like this issue does. Wizards refusing to deliver a common-sense commodity market to the players is indicative of an underlying failure to truly comprehend their product. How could a system that was outdated the day it was released still be in place today when the inevitable results would have been so clear even at the time of its conception? MTGO has no shortage of software flaws and misguided policies, but this is a disservice to the Magic community unlike any other in recent memory.

Nearly all of MTGO’s other problems can be fixed with software updates and policy changes. The solution to this problem, though, is what we all deserve and Wizards refuses to give us: A brand new Magic Online experience.

Track your collection's value over time, see which cards moved the most, track wishlists, tradelists and more. Sign up at MTGPrice.com - it's free!